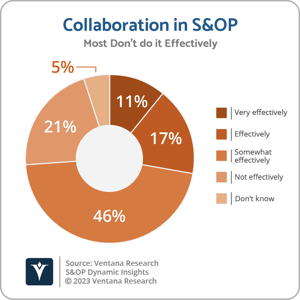

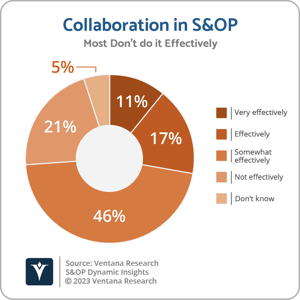

Organizations engage in collaborative supply chain planning in order to have more accurate, timely and actionable information, including forecasts and stock-on-hand. The objective is to achieve lower costs and reduce risk while ensuring order fulfillment to achieve optimal supplier and customer relationships. Unfortunately, our research shows that that few companies manage collaboration well in their sales and operations planning (S&OP) processes. Today, S&OP software has become more accessible and powerful, enabling users to forecast future supply and demand chain conditions with greater accuracy and agility. Often, the value of these projections and the plans built on them can be enhanced when suppliers and customers freely exchange information with each other. Collaborative supply and demand planning may sound like a win-win, but in practice, it has proven to be difficult to achieve. Nonetheless, in some industries, trading partners would be well served by data sharing. In these instances, one practical approach would be creating a data exchange hub that provides credentialed members access to supply and demand data in a highly controlled manner. The technology that can facilitate this is relatively new and can be used to substantially eliminate the technical difficulties that previously stood in the way of useful data sharing.

From the beginning of the Industrial Age until about the 1960s, vertical integration was thought to be the most dependable way to achieve balance in supply chains and lower costs, even if in practice it wasn’t always reliable.  That’s because conflicting incentives, such as minimizing unit production costs in one business unit versus minimizing working capital in another that consumed the output, diluted the value of such integration. As computing and communications systems grew more powerful and interconnected in the second half of the 20th century, incentives to vertically integrate diminished. A long list of transformative innovations including container shipping and the internet, as well as ever more liberal trade, made it possible for product companies to federate supply, demand and logistics in order to concentrate on the parts of the value chain where they had a competitive advantage or simply an ability to compete. These arrangements, however, also can complicate planning and execution if access to trading partners’ forecasts is limited.

That’s because conflicting incentives, such as minimizing unit production costs in one business unit versus minimizing working capital in another that consumed the output, diluted the value of such integration. As computing and communications systems grew more powerful and interconnected in the second half of the 20th century, incentives to vertically integrate diminished. A long list of transformative innovations including container shipping and the internet, as well as ever more liberal trade, made it possible for product companies to federate supply, demand and logistics in order to concentrate on the parts of the value chain where they had a competitive advantage or simply an ability to compete. These arrangements, however, also can complicate planning and execution if access to trading partners’ forecasts is limited.

It's worth noting that in some instances, supply chain information sharing may be irrelevant or have limited value. This is the case in any market where there are enough suppliers or the ingredients or parts of a bill of materials are flexible enough to enable a rapid adaptation to a change in conditions including quantity and pricing. The importance of collaboration is also diminished with short supply chains, and where external events such as weather, political instability or logistical uncertainties have a limited potential impact to disrupt ordinary business. It’s also less essential in markets where supply and demand quantity and pricing for an item are relatively predictable — that is, there is a sufficiently narrow standard deviation around a relatively bell-shaped distribution curve.

The opposite is true where those conditions do not prevail, and that’s when collaboration between buyers and sellers in a supply chain can pay off. Sharing supply and demand data in buyer-seller relationships can, in theory, be mutually beneficial. However, two main obstacles usually get in the way of information exchanges. One is rational human behavior. Either or both parties may be unwilling to share information candidly because of competitive or economic considerations. The second is logistical. Even when both parties agree to sharing information, they may not be able to streamline the exchange to a point where it is reliable and practical. Often, it is difficult to gather the relevant data internally and it may not be easily consumed at the other end. Technology can address the latter issue but not the former.

Information sharing and collaboration come in three basic forms. One is sharing without collaboration, where a supplier or customer communicates data that best serves its interests. The provider may shade a forecast to be optimistic or conservative depending on what serves its best interests, or it may publish a limited set of data, which may not be very useful. A second, deeper level of sharing is built around some level of information sharing, measured in depth or frequency, where there are some incentives for openness and accuracy. These forecasts may be prepared with the best of intentions but do not come with an obligation to buy or supply anything. So, beyond reputation risk, the penalties for a lack of candor or rigor in forecasting are small. A third level of collaboration comes with fulfillment obligations. These may vary in their extensiveness, chiefly measured in the length of the period and penalties for non-fulfillment. The focus here is on the exchange of information between buyers and sellers in a supply chain, whether or not there are contractual obligations involved.

What information should participants agree to share? The basic recommendation is to apply the 80/20 rule, identifying the information that is most critical to the participants’ supply chain management and their S&OP efforts. For example, it could include those items that have the potential to significantly disrupt the supply chain, where business risks can be mitigated by the sharing of information. This includes long lead items, ones that require lengthy reaction times to adapt to disruptions or unexpected events. Such data is useful where supply or demand is limited to a handful of companies where there are distribution constraints, ones where severe weather has been a factor in the past or where there is risk of disruption caused by political events. It’s important to acknowledge that no amount of collaboration will fully offset black swan events such as the recent pandemic. Through most of 2022, Boeing and Airbus sat on billions of dollars of finished airframes that could not be delivered because the engine manufacturers were unable to increase their production fast enough, mainly because of labor shortages.

Another area for data sharing includes items that can have a significant negative economic impact if forecasts prove to be inaccurate. This would be the case where there would be a noticeable impact on manufacturing or distribution efficiency, a significant degradation of working capital efficiency or increased costs, or a negative impact on fulfillment rates or the ability to honor contractual obligations. Sharing information where no such exchange existed in the past might also provide opportunities to lower economic costs along the value chain.

Even when participants in a supply chain agree to share information, the agreement is typically bilateral and involves point-to-point exchanges. This ad-hoc approach is problematic because it imposes a data management  burden that is usually time consuming. It also poses timeliness and accuracy risks. One alternative is to create a data hub managed by a neutral and trusted third party such as an industry association, but this can be hard to arrange since such associations may lack the expertise and have limited incentives to do so. Moreover, the process can be lengthy because of the way in which these organizations work. An example of where it’s happening is in the shipping industry, where the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA) is establishing standards for a common technology foundation that enables global collaboration.

burden that is usually time consuming. It also poses timeliness and accuracy risks. One alternative is to create a data hub managed by a neutral and trusted third party such as an industry association, but this can be hard to arrange since such associations may lack the expertise and have limited incentives to do so. Moreover, the process can be lengthy because of the way in which these organizations work. An example of where it’s happening is in the shipping industry, where the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA) is establishing standards for a common technology foundation that enables global collaboration.

Information collaboration in supply chains is more practical than ever, but it’s likely to take many years to eliminate existing technological barriers to such sharing. Ventana Research asserts that through 2026, fewer than one-fifth of organizations will participate in a data-hub enabled supply chain information collaboration. I recommend that supply chain professionals in industries where there is already some degree of information sharing to find a way to create an information hub, either through an industry association or some other third-party group.

Regards,

Robert Kugel

That’s because conflicting incentives, such as minimizing unit production costs in one business unit versus minimizing working capital in another that consumed the output, diluted the value of such integration. As computing and communications systems grew more powerful and interconnected in the second half of the 20th century, incentives to vertically integrate diminished. A long list of transformative innovations including container shipping and the internet, as well as ever more liberal trade, made it possible for product companies to federate supply, demand and logistics in order to concentrate on the parts of the value chain where they had a competitive advantage or simply an ability to compete. These arrangements, however, also can complicate planning and execution if access to trading partners’ forecasts is limited.

That’s because conflicting incentives, such as minimizing unit production costs in one business unit versus minimizing working capital in another that consumed the output, diluted the value of such integration. As computing and communications systems grew more powerful and interconnected in the second half of the 20th century, incentives to vertically integrate diminished. A long list of transformative innovations including container shipping and the internet, as well as ever more liberal trade, made it possible for product companies to federate supply, demand and logistics in order to concentrate on the parts of the value chain where they had a competitive advantage or simply an ability to compete. These arrangements, however, also can complicate planning and execution if access to trading partners’ forecasts is limited. burden that is usually time consuming. It also poses timeliness and accuracy risks. One alternative is to create a data hub managed by a neutral and trusted third party such as an industry association, but this can be hard to arrange since such associations may lack the expertise and have limited incentives to do so. Moreover, the process can be lengthy because of the way in which these organizations work. An example of where it’s happening is in the shipping industry, where the

burden that is usually time consuming. It also poses timeliness and accuracy risks. One alternative is to create a data hub managed by a neutral and trusted third party such as an industry association, but this can be hard to arrange since such associations may lack the expertise and have limited incentives to do so. Moreover, the process can be lengthy because of the way in which these organizations work. An example of where it’s happening is in the shipping industry, where the